Afghanistan, a country which despite being often associated with conflict, oppression, and turmoil, abounds with a rich cultural tradition in arts, crafts, and music. From oral poetry and songs to world-renowned crafts and embroideries, the Afghan people have kept alive their centuries-long traditions amidst the restrictions imposed by the Taliban.

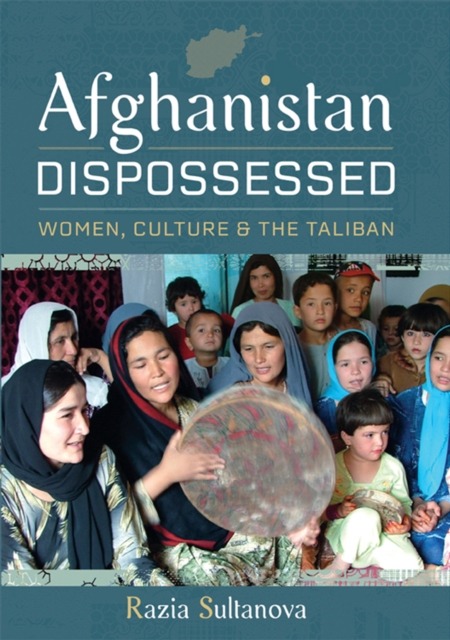

In her latest book, Afghanistan Dispossessed: Women, Culture and the Taliban, musicologist and social scientist Dr Razia Sultanova (Cambridge Muslim College Research Fellow 2019-2024) portrays a vivid, in-person account of the country’s social, political, and cultural developments and their impact on the role of music, especially pertaining to women who, for the most part, have been highly neglected and marginalised as a result of war and conflict. The book is based on deep fieldwork and academic analysis with extensive eyewitness accounts from conversations with a wide variety of Afghan men and women.

Music, its Ban and Mysticism

The Afghan people are passionate about poetry and music. As Sultanova explains, “Afghanistan has an ancient tradition of songs built on its rich culture of poetry, ranging from war, heroism, and epic tales of life in this harsh land, to delicate love stories”. During the Taliban’s regime, between 1996 and 2001, TV and music were banned under their interpretation of the sharīʿa as they were deemed morally corrupt and, if discovered in a household, the head of the family would be arrested and punished (they have again returned to power since 2021).

Likewise, Sufi devotional practices have long been considered an integral part of Islam in Afghanistan across social strata and geographic locales. The Chishti Sufi Order popular in Afghanistan considers music to be an effective route to reach God, making music an integral component of Sufi gatherings in the country.

Likewise, Sufi devotional practices have long been considered an integral part of Islam in Afghanistan across social strata and geographic locales. The Chishti Sufi Order popular in Afghanistan considers music to be an effective route to reach God, making music an integral component of Sufi gatherings in the country.

Women’s Arts of Inward and Outward Beauty

Beyond and behind the burqa (the Afghan chadri) are women who are hospitable, relaxed, and confident. Afghan women enjoy a strong aesthetic sense and appreciation of beauty. In fact, women learn tailoring, carpet-making, and embroidery in childhood; as adults, they account for 87 per cent of the handcraft workforce. Fruits, flowers, and birds are the main motifs embellishing the bright and colourful handcrafts designed using silk to beautify plain cotton materials. As Sultanova highlights, many women consider their employment in these crafts as a kind of therapy that is often accompanied by singing. Afghan women sing in gatherings, festivities and on their recurrent daily journeys to fetch water, which has the added benefit of educating their children in Afghan culture, history, and religious teachings. For instance, this wedding song’s lyrics are adorned with deep spiritual resonances:

The chain made by a jeweller

Is impossible to tear apart.

The destiny given by God

Is impossible to break down.

Music and National Identity: The Uzbek Contribution

As the third largest ethnic population of Afghanistan, the Uzbeks have enriched the country’s cultural heritage, and particularly the Northern Afghan regions, through poetry, songs, and performances commemorating common historical events. As Sultanova elucidates:

Styles of Uzbek music performed in Northern Afghanistan vary, ranging from court to folk traditions, thus covering two rather opposite aspects of culture represented by the highly professional, classical style (Maqam) which has originated from the cities to bard-style music played by the nomads and wandering musicians known as Bakshy. Maqam style music is built on a foundation of oral transmission called ‘Ustoz-Shogird’ and involves teaching based on personal contact between teacher and pupil without any transcription provided. This method has remained popular to this day.

In the last decades, Uzbek music and culture have been influenced by historical, political and religious events, on the one hand, and by the traditional vs modern, Eastern vs Western waves, on the other hand. Similarly, as Ustad, or Master, Said Ghaffar Kamoliddin (1930-2010) points out, the new generations are renouncing centuries-old music traditions. For instance, ancient instruments, like the dutar (a long-necked lute with two strings and frets), are being abandoned for commercial instruments or, as he defines them, instruments of ‘no nation’. This threatens the preservation of the Uzbek culture, history and national identity, both within and beyond Afghanistan.

Author’s Message

In her study, Dr Sultanova has demonstrated how, in a country facing ongoing turmoil and instability, music comprises a source of healing, faith, and meaning. Music, crafts, and poetry represent for many their main source of income, an outlet for creativity and, at times, personal resilience (exemplified by the female pop-singer Elaha). With the ongoing dangers of internal unrest and the cultural influence of an increasingly globalised world, traditional music in Afghanistan, like other cultural domains, is on the brink of extinction. Dr Sultanova’s work of documenting, recording, and sharing these stories is a vital step in averting this prospect.

Dr Razia Sultanova has studied and worked at both the Tashkent and Moscow State Conservatories and worked at the Russian Institute of Art Studies in Moscow. In 1994 she moved to reside in the UK and work at the University of London and since 2008 has worked at the University of Cambridge. She is the author of four books and five edited volumes (in Russian, French and English) on Central Asian gender, religion and music. She has been a visiting Professor at Moscow State Conservatory (Russia), at the Kazakh National University of Arts (Nur-Sultan), and at the Khoja Ahmet Yassawi Kazakh-Turkish University (Kazakhstan/Turkey).

Dr Razia Sultanova has studied and worked at both the Tashkent and Moscow State Conservatories and worked at the Russian Institute of Art Studies in Moscow. In 1994 she moved to reside in the UK and work at the University of London and since 2008 has worked at the University of Cambridge. She is the author of four books and five edited volumes (in Russian, French and English) on Central Asian gender, religion and music. She has been a visiting Professor at Moscow State Conservatory (Russia), at the Kazakh National University of Arts (Nur-Sultan), and at the Khoja Ahmet Yassawi Kazakh-Turkish University (Kazakhstan/Turkey).